April 18, 2023

Review: Thomas Adès's 'Dante' Ballet Takes Us to Hell and Back

Tim Pfaff READ TIME: 5 MIN.

Thomas Adès thinks big. Devotees of the composer, conductor, and pianist can hardly complain about his busy public profile. Still, for fans of his large-scale works, hell is the relative rarity of hearing and seeing them fully staged.

Virtually everything he has composed has been recorded, and god knows the DVD has done its part to correct the imbalance in the stage spectacles. But as we wait for the video of Adès's full-length ballet "Dante" (you know somebody's got it), we have, as a major compensation, the new live recording of the 90-minute piece by the Los Angeles Philharmonic under its departing music director, Gustavo Dudamel (Nonesuch).

All the World's Stages

Because Adès's operas have been staged by the world's major companies, he's often called an opera composer, a somehow reductive designation for a composer who doesn't seem to have skipped a single genre for his work. But then, he's also called the most important gay composer since Benjamin Britten.

I depart from that all-but-unanimous opinion only because it overlooks George Benjamin, a far less prolific out Brit who nonetheless also works as an all-around musician, and whose eagerly awaited new opera, "Picture a Day Like This," takes center stage at this summer's Aix Festival. Benjamin is Emily Dickenson to Adès's Walt Whitman.

Adès's first opera, "Powder Her Face," has gained traction throughout the musical world (including at the Bay Area's enterprising West Bay Opera), partly because it calls for smaller forces, but perhaps more famously because it features opera's first onstage blowjob.

"The Tempest" is arguably the first reworking of the story in all of operatic history not to be skunked by that most musical of Shakespeare's plays. For all its brilliance, "The Exterminating Angel" left a classic film, hailed by the music press and professionals as the magnificent composition it is, largely in the dark while simultaneously keeping the larger section of the audience not steeped in the ways of new music scrambling just to keep up.

Did He or Dante?

One of the many offspring of the 2021 eight-millenia Dante Year, Adès's new ballet gathered steam under the auspices of The Dante Project by the Royal Ballet Covent Garden, where it was fully staged in October 2021. It is now slated for the Paris Opera, where, not incidentally, Dudamel has been announced as music director-designate and has been conducting for years.

But from its conception it's been considered a work that can hold its own in a symphony-only performance. The brilliant new recording is all the proof needed.

Adès is far to great a re-creator to follow Dante's "Divine Comedy" slavishly, but the work does divide into the sections "Inferno," "Purgatorio," and "Paradiso," all newly drawn into the central concerns of our century without sacrificing the themes and elements that make it one of the great poems of all time.

Satan himself doesn't make his splashy onstage entrance until the last movement of "Inferno," but, as in John Milton's English epic poem, "Paradise Lost," he's the center of attention and gets all the best lines.

If, as some have alleged, Milton's "Paradise Regained" is a paler sequel, so, too, Adès's "Purgatorio" and "Paradiso" are shorter, if, in Adès's case, no less compelling. Fans of the requiem as a musical form pretty much agree that it is the "Dies Irae" ("Days of Wrath") that's the most exciting.

Foot-tapping in the Audience

While there's nothing "easy" about Adès's characteristically dense score, it's one of the composer's most transparent, in the sense that its music tells a story through dance tropes that audiences, too, can readily follow by the colorful movement titles. Nearly the full panoply of the kinds of music in "Dante" is audible in its promo track, "The Thieves – devoured by reptiles."

The other classes of sinners condemned to hell's circles all get their time out of the sun. Perhaps I'm "hearing in" in finding "The Deviants – on burning sand" more compassionate, less hellfire and brimstone, than today's far right would tolerate. Adès is renowned for testing – more, challenging – the limits of instruments, very much including the piano and voices.

While that might hint at a surfeit of forbidding shrieks, what is remarkable about the "Dante" score is the combination of kaleidoscopic sonorities from across the aural range but in effects that have audible causes. A lesser composer could have gotten away with relentless noise, which could not be farther from the rich variety of these musical ideas.

You're never unaware that this is music for the stage, specifically for dance, the most amazing aspect of which is that it imposes no simplifications on the score. And it's not past imagining that land-lubber audience members might be caught doing some toe-tapping of their own.

Such strictures as dance rhythms impose seemed to have worked to the benefit not only of the dancers but also of the composer and audience. Adès considers the piece to be, among other things, his response to the Tchaikovsky ballet scores the world adores, and he, too, has conducted. To be sure, there's no thumbing his nose at the genius of a predecessor gay composer.

It's central to Adès's artistic creed that music, and sounds, are physical things, and that composition entails, among other things, the manipulation of large blocks of sound (some of it so "soft" it's at the limits of audibility).

Imported sounds have their place, too. Wending its way throughout "Purgatorio" is a solo-male voice, whose music mirrors that of the bagashot. (For comparison, think of the wail of muezzins calling the faithful to prayer in mosques around the world.) The bagashot is associated with the Syrian-Jewish diaspora, and the recording blended into the textures here comes from the Ades Synagogue in Jerusalem, the links to Adès's own family tradition explicit and true.

There's no overstating the astonishing richness and variety in the music of "Dante." It does not play itself out by the advent of "Paradiso," the single, continuous 26-minute final movement. Adès has called it "dazzling, strange, almost pure geometry."

It could be expected that the music of "Paradiso" marks an ascent from "hell" to "heaven." Adès capitalizes on the idea with some of the score's most captivating music. Of course, there are limits to the reach of physical sound, but somehow Adès manages to make the otherwise comparatively repetitive music of the spheres seem to ascend continuously, a transfixing, inviting stairway to heaven.

The Dude and his Angelenos earn the highest accolade purveyors of theatrical music can receive, one all the more commendable in an audio-only version. You almost forget they're there.

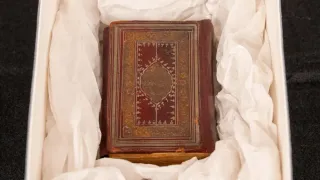

Thomas Adès, "Dante," Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra, Gustavo Dudamel, conductor, Nonesuch, two CDs, $24.98 www.nonesuch.com

Help keep the Bay Area Reporter going in these tough times. To support local, independent, LGBTQ journalism, consider becoming a BAR member.