4 hours ago

Joel Kim Booster Marries John Michael Sudsina in Joyous San Francisco Ceremony

READ TIME: 3 MIN.

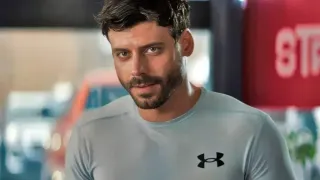

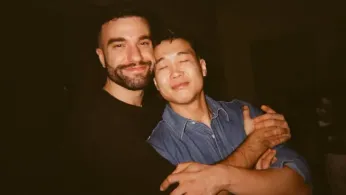

Joel Kim Booster, the acclaimed comedian, actor, and writer known for his roles in "Fire Island" and "Loot", married his longtime partner, John Michael Sudsina, a video game producer for Riot Games, on December 30, 2025, at the Exploratorium in San Francisco. The ceremony, officiated by Booster's childhood best friend, Rev. Sarah Casey, an ordained Methodist minister, drew 167 close family members and friends, creating an intimate yet celebratory atmosphere.

The couple's love story began in 2021 during a vacation in Puerto Vallarta, Mexico, a vibrant destination popular among LGBTQ+ travelers. Introduced by mutual friends at a club, Booster and Sudsina quickly became inseparable, dubbing themselves "vacation boyfriends"as they spent the rest of the trip together. Booster later recounted to The New York Times, “We were pretty much scream-whispering stories into each other’s ears at the very loud nightclub, just telling every anecdote from our lives. Which now, in hindsight, is very us. ”

Despite living in different cities—Booster in Los Angeles and Sudsina in San Francisco—their connection deepened rapidly. They maintained daily contact, watching television over FaceTime and sharing constant conversations. Just two weeks after meeting, Booster publicly declared his feelings on his podcast, stating, “So I’m in love with this guy. I met him two weeks ago. I’m going up to visit him at SF Pride. Ostensibly, I’m going there to see my friends. But that’s a lie, ” a moment Sudsina found endearing.

Their relationship profoundly influenced Booster's creative output, particularly his 2022 film "Fire Island", a modern queer adaptation of "Pride and Prejudice" that earned him Emmy nominations for Outstanding Television Movie and Outstanding Writing. Booster shared an early director’s cut with Sudsina, who was moved to tears; the script was rewritten based on conversations from their Puerto Vallarta trip, including a memorable day spent talking in a cabana. Booster proposed to Sudsina in 2024 on Jeju Island in South Korea, Booster's birthplace before his adoption as an infant, adding a deeply personal layer to their commitment.

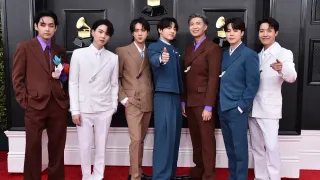

The wedding venue, the Exploratorium—a renowned interactive science museum—reflected the couple's shared sense of playfulness. Booster told The New York Times, “We both have a very big sense of play, and that is sort of the ethos of the Exploratorium. ” Emotional speeches were delivered by prominent queer figures in comedy and entertainment, including Zane Phillips, Mitra Jouhari, Ahmed Zaeem, Phil Tassin, Matt Rogers, and Bowen Yang. Additional attendees included Margaret Cho, Michaela Jae Rodriguez, and others from Booster's projects like "Fire Island" and "Loot".

Following the ceremony, Booster shared his joy on Instagram, posting photos by Mandee Johnson for The New York Times: “Feeling very lucky that I can honestly say my wedding was the best day of my life, no contest. I’ve never felt so certain and so loved. .. . I’m just really happy. ” Sudsina, who plans to take Booster's last name, reflected on their bond: “I feel when I’m with Joel, I’m in a rom-com. It’s always an adventure. And I love that we both have already worked through so much and continue to meet new versions of each other and continue to grow together. I think he’s going to be an amazing father, an amazing partner, an amazing friend. ”