Apr 5

Gayle King Goes There with Gay Slur... and Network Censors Let It Pass

READ TIME: 2 MIN.

Perhaps it is a sign that woke culture is on the wane that Gayle King felt comfortable enough to use a gay slur on the network chat show "CBS Mornings," and the censors let it pass.

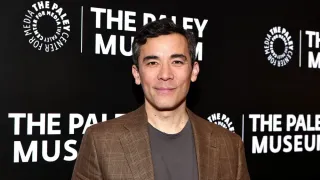

King was speaking with queer comic Matteo Lane, who had joined her to promote his new book, "Your Pasta Sucks," which he said exemplified his penchant for "being funny in the kitchen" in addition to his work as a comic on stage – which King excitedly said she wanted to discuss with him, Entertainment Weekly reports.

"Can we talk about the stand-up? Can I just say one joke? I hope I don't get in trouble," King said before moving forward with the quote. "You do a riff about white women who approached you, and they said something about cooking, and you said, 'What in the f----try are you talking about?'"

The footage (which is still available on user-shared recordings on X) sees Lane laughing with his hand over his mouth, as King exclaimed, "I thought that was hilarious. What does that mean?"

Watch the full interview with the term bleeped.

Lane responded: "I love you, Gayle King. It means exactly what you think it means. White women, they're fine during the day, but they have one sip of a rosé and they're like, 'Tonight's about me!' They won't stop, I'm telling you. Horrible."

"The show didn't censor the word on the live telecast or when the clip was uploaded to YouTube, though the network deleted the video from the website after Entertainment Weekly reached out for comment on Friday," writes EW.

Bob the Drag Queen, the "RuPaul's Drag Race" winner and a friend of Lane's, retweeted King's comment, calling it "honestly ironic."

Will her comment turn up on a dance remix next?